The Workhouse

Two hundred years ago, if you were disabled, or old, or an orphan, or poor, pregnant and unmarried, or had just fallen on hard times, there was only one place for you – the workhouse.

The workhouse system had operated since Elizabethan times. Parishes were individually responsible for the care of their own poor, and the help given was paid for from a “poor rate” levied on local taxpayers. The system was operated by a committee known as the vestry.

In Walthamstow, the vestry decided to build a specially designed workhouse on church land in 1730. The statement that was inscribed over the door, “if any would not work neither should he eat”, summed up the ethos of the place. About forty of the local poor were taken to live in “the house”, under the care of a master and mistress. By the standards of the time, the conditions were not bad – the food, although plain, was adequate, and the paupers were given decent clothes. However, the house was overcrowded, and the work was monotonous.

In the eighteenth century the vestry were sometimes generous towards individuals. Old men and women were nursed in their own homes; a horse was hired for a pauper who had got a new job; checks were made to follow up on young boys starting apprenticeships to make sure they were happy and progressing in their chosen trade.

But in 1834 everything changed. The new poor law meant that groups of parishes must join together to set up union workhouses, and that these were to be the only means of relief for the poor of their areas. So Vestry House became a police station, and the West Ham Union workhouse came into being.

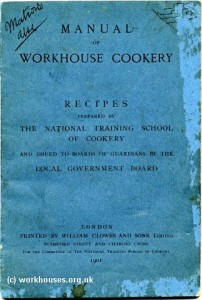

The new workhouse in Leyton was huge and well designed, with separate accommodation for men, women, children, the sick and the elderly. The infirmary alone had 200 beds. Inside, the accommodation and food were as austere as the Poor Law Commissioners had intended.

When they went into the workhouse, families were separated, and children over the age of seven were sent to the school that was part of the site. The able bodied were made to work, at occupations such as picking oakum to make rope, and breaking stones. And women were expected to become unpaid nurses.

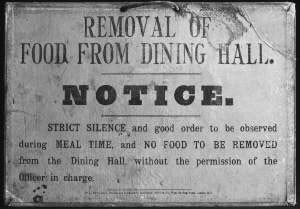

Meals, monotonous and barely enough to stave off hunger, were taken in silence, and anyone who broke a rule was deprived of food for 24 or 48 hours. These were the conditions made infamous by Charles Dickens’ “Oliver Twist”

As the nineteenth century went on, a series of scandals meant that conditions were improved. By the time the Dyson family spent a year in the workhouse, there was a good school on the site, food had improved, and it was accepted that neither children nor the elderly were to blame for their condition. But the workhouse was still regarded with shame and horror. Each winter, all over the country, a few people preferred to die of starvation and cold rather than seek help.

As the nineteenth century went on, a series of scandals meant that conditions were improved. By the time the Dyson family spent a year in the workhouse, there was a good school on the site, food had improved, and it was accepted that neither children nor the elderly were to blame for their condition. But the workhouse was still regarded with shame and horror. Each winter, all over the country, a few people preferred to die of starvation and cold rather than seek help.

In 1913 the term “workhouse” was abolished, old age pensions had been introduced and, in Waltham Forest, the Poor Law Guardians had fought to build Whipp’s Cross Hospital, a state of the art facility for any local person who could not afford to pay for medical care.

The scene was set for the modern welfare state. But for several decades older people continued to regard the memory of the workhouse with horror.