He was one of the last three veterans who could remember serving in the First World War, and although for most of his long life he had kept his wartime experiences to himself, in later years he was persuaded to talk about his life and memories, as a tribute to those who had died in that War. Assisted by a member of the veterans association, and with a prodigious memory, he wrote an autobiography, starting as a small child in a Britain still ruled by Queen Victoria.

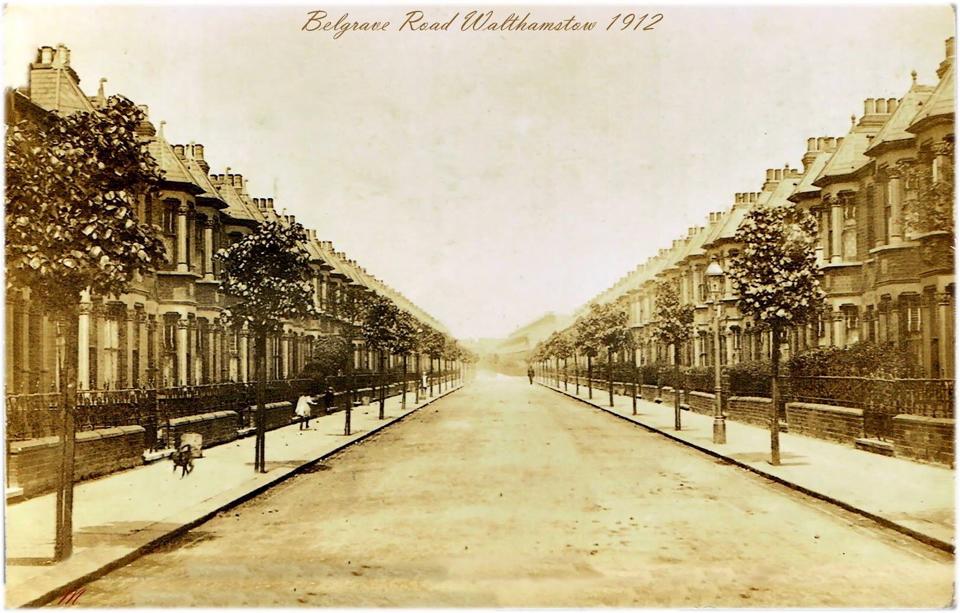

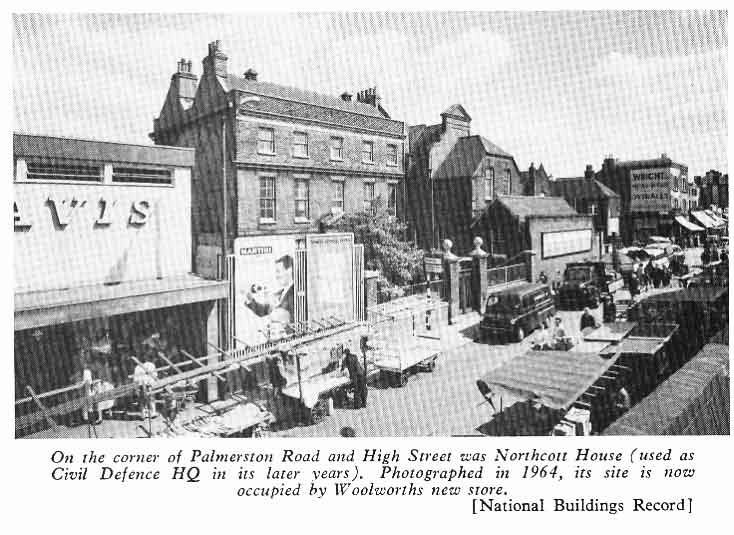

He described the world he lived in as a small boy

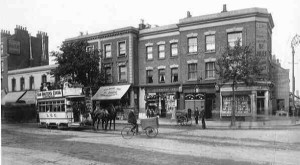

‘There were individual tradesmen’s carts delivering bread, milk ,groceries and coal. Milk was carried in steel containers holding up to 15 gallons and was dispensed to customers who brought their own containers to carry it home’

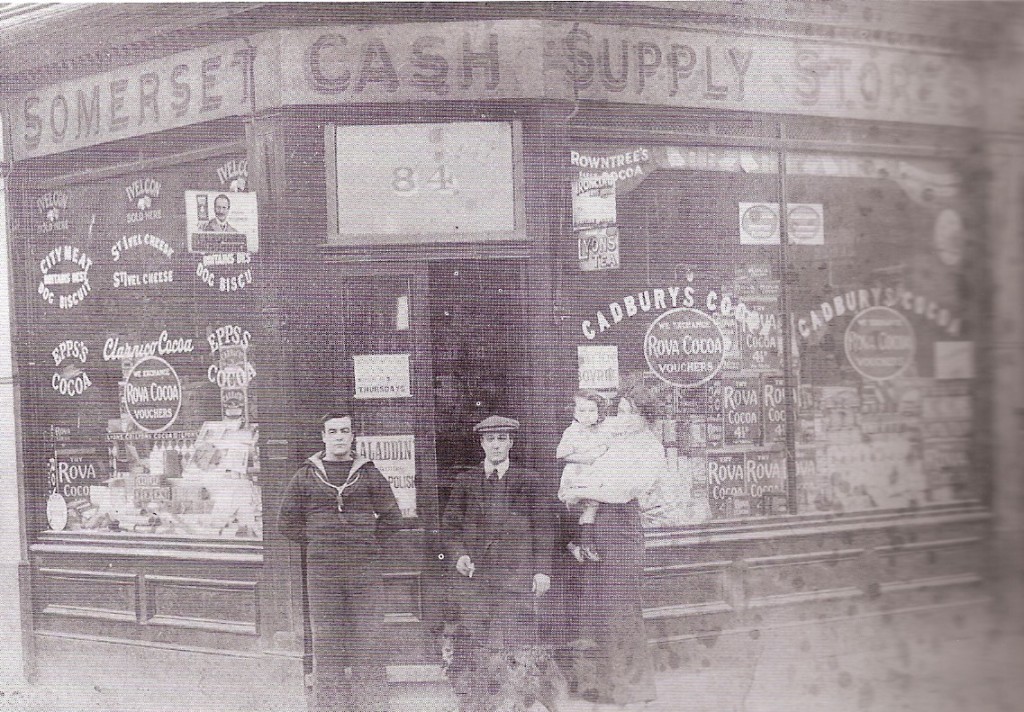

‘Shops had counters and shelves holding jars tea, cocoa and biscuits and so forth. sugar, rice and dried fruits were kept in hessian sacks and weighed out on demand. Carcasses hung from hooks at the butchers and there was often a pigs head staring out at you’

His own father had died of tuberculosis when Henry was three, and he was aware of the prevalence of life-threatening illness, in the days before the National Health Service and antibiotics.

‘Tuberculosis, diphtheria and fevers were common and often fatal – as was the case with the early death of my father. Cancer never appeared on death certificates as it couldn’t easily be detected.

‘ Funerals were more commonplace, and almost always started from home – it was the natural thing to do’

He had many memories of his early school days

‘I went to Gamuel Road School in Walthamstow at the age of five, in 1901…’of the 40 or more children in my class the majority were poorly dressed, had no shoes, and quickly resorted to fights

‘Boys wore short trousers until their legs got hairy. girls wore combinations (all in one vest-and-pants) I know that because I saw them on washing lines. Shoes were always a problem, at least well fitting shoes were. I have had two hammer toes all my life due to badly fitting shoes.

‘At school we were taught to read and write. … We had sandboxes to write in. I will always remember the smell given off by the sand. It ponged. We had to trace the letters in sand using a metal skewer. and there was trouble if anyone spilled the sand. ….. any books we had were shared and dog eared

‘I left Gamuel Road School at Easter 1902 and went to Bessborough Road School. In June I remember watching soldiers home from the Boer War parading in front of the Town Hall in Hackney – troops known as the Clapton volunteers.’

He remembered holidays with his grandparents on the Isle of Wight, and in Scarborough (they went to Scarborough by sea!) coping with the local school bully and earning money for football lessons by selling horse manure door to door as garden fertiliser – a piece of early enterprise that only stopped when someone stole his home made cart. He and his mother went to Hampstead Heath for the August Bank Holiday Fair every year, and played football in the street – though he secretly preferred cricket. He joined the new Carnegie Library in Manor Park on the day that it opened in 1905, and got issued with ticket number 13.

At the age of nine, he left Walthamstow to live with his mother again, in Clapham and continued at school there.

He left school at the age of 15 and after a short spell as a scientific instrument maker, went into work with coach builders, working on cars; a career he would follow for the rest of his working life.

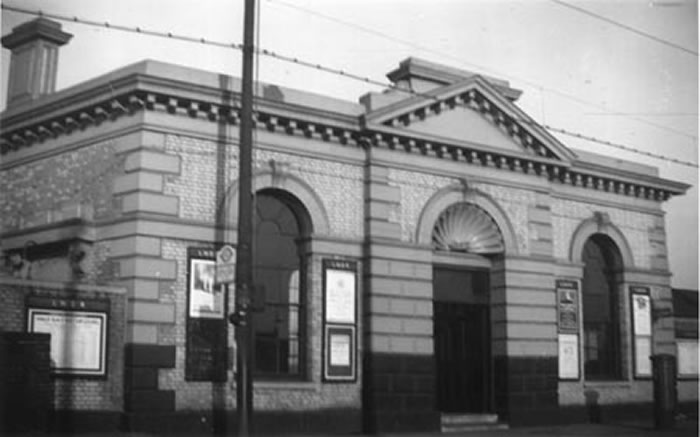

When the First World War broke out, he tried to volunteer as a dispatch rider (he had his own motor bike) but promised his mother that he would not join up. When she died of cancer in June, 1915, he considered himself released from his promise, and joined the royal Naval Air Service, doing his mechanic’s training at Chingford.

He became a skilled mechanic, and even went up in a plane – he recalled that everyone covered their face with Vaseline or engine oil to try and protect it from the cold and wind. – and was working on ships launching planes from deck a the battle of Jutland, and remembered ‘ seeing shells ricocheting across the sea’ Later in the war he was stationed in Northern France, as an observer and bomb launcher, and saw front line troops preparing to go ‘over the top’.

He became a skilled mechanic, and even went up in a plane – he recalled that everyone covered their face with Vaseline or engine oil to try and protect it from the cold and wind. – and was working on ships launching planes from deck a the battle of Jutland, and remembered ‘ seeing shells ricocheting across the sea’ Later in the war he was stationed in Northern France, as an observer and bomb launcher, and saw front line troops preparing to go ‘over the top’.

‘They would just stand there in 2ft of water in mud filled trenches, waiting to go forward. They knew what was coming. It was pathetic to see those men like that’

The royal Naval Air Service became the RAF in 1918, but Henry always thought of himself as a ‘Navy Man’

He married in 1918, and after the war lived for many years in Forest Gate, before moving permanently to the South Coast, near Brighton after the Second World War.

He came to public notice in 2005 when, with two other survivors of the First World War, he attended the Remembrance Day Service, and from then on until the end of his life he would give talks to schools and other groups about his experiences. He attributed his long life to ‘cigarettes and whisky and wild, wild women ‘ though he also acknowledged that the only woman that he had ever kissed was his wife, Dorothy.

When asked what he thought about the First World War, he replied, ‘War’s stupid. Nobody wins. you might as well talk first; you have to talk last anyway’