For centuries Walthamstow’s dead were buried in the graveyard of the parish church of St Mary. There was easily enough space there to provide burial places for the needs of a small town.

In later years, with the arrival of Nonconformist churches and chapels in the eighteenth century, each had a burial ground for their own congregation. And as Walthamstow grew, three new Church of England churches were built, each with a graveyard of its own.

In 1870 the local authority agreed in principle to set up a new cemetery. The first thing they did was to appoint a committee, and this began to meet regularly to discuss the project.

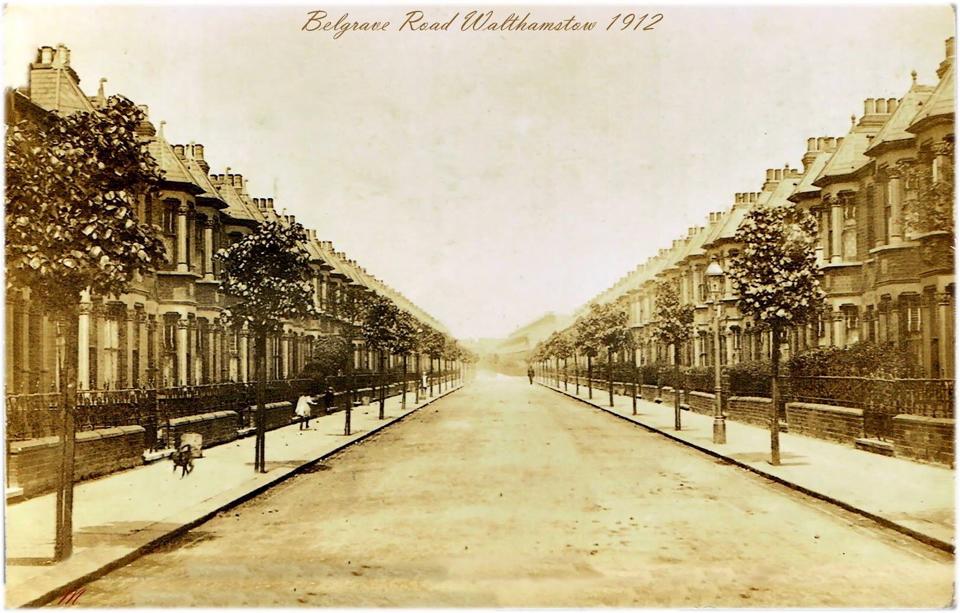

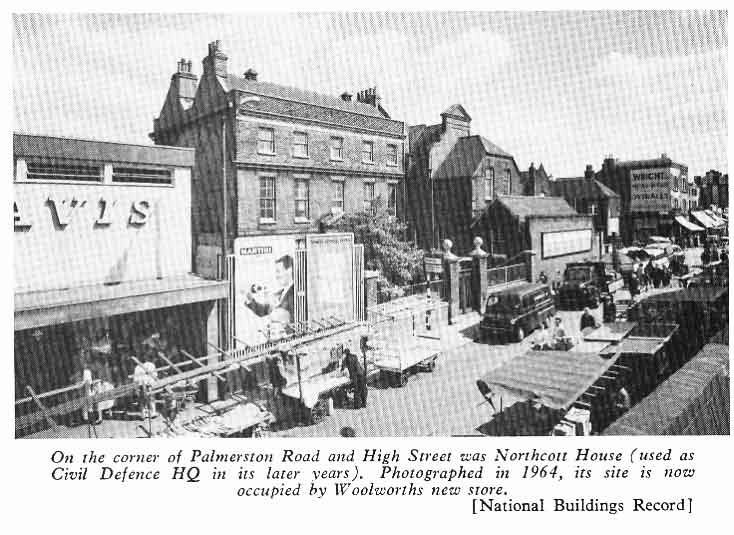

After many meetings and some arguments, and after rejecting a number of suggestions as impractical, the committee finally agreed to buy eleven acres of land near Markhouse Common for £5,000. The owner, a Mr Innes, had asked unsuccessfully for an extra £500. The price included the timber, plus a right of way from Hoe Street to the site.

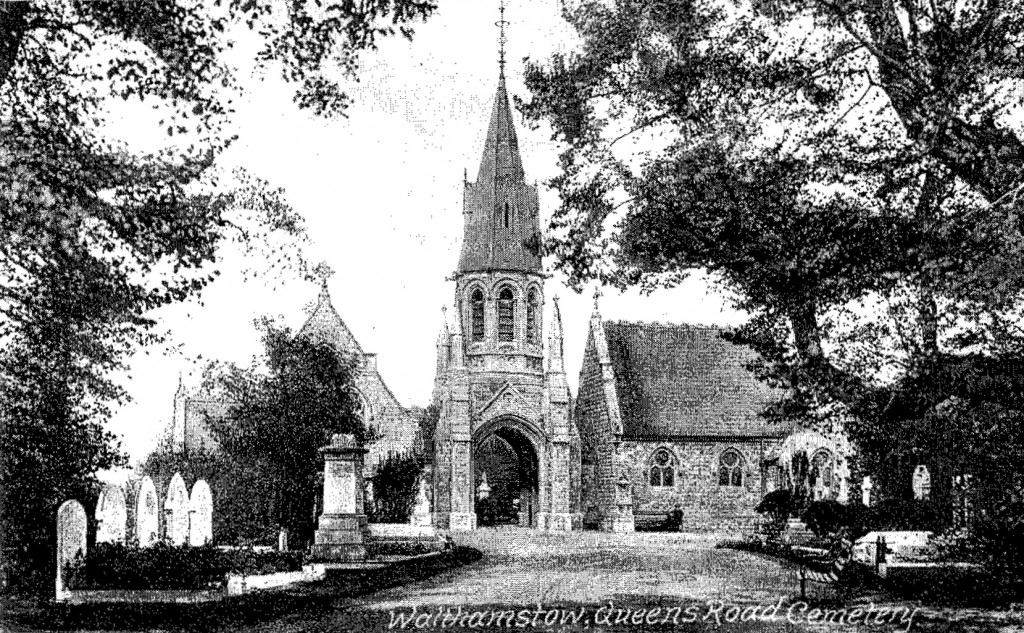

The committee now started to meet once a fortnight – there was a lot of organise. They decided the cemetery should be divided into two sections, one for members of the Church of England, the other for everyone else. Similarly, there were to be two chapels, one for Anglican (that is, Church of England) services, the other, for Nonconformists, that is, all other Christians except Roman Catholics (who had a church and graveyard in Shernhall Street).

By this time there had long been a Jewish community in the area, and they had had synagogues and burial grounds since the early eighteenth century – there were several in Hoxton and Hackney. The first mosque in England was to open in 1924, in Southfields. In the late nineteenth century there were a few people in Walthamstow who may have been Hindus, Muslims or Sikhs – but they do not seem to have settled here permanently.

So two chapels were going to be enough. The committee decided there should also be a caretaker’s house and various outhouses, and that the cemetery should be fenced all round, with impressive wide entrance gates and main pathway.

It was also agreed that the Coroner’s Court should meet at the cemetery whenever an inquest into an unexplained death was necessary. So a meeting room was added to the list of requirements. Six architects were invited to tender for the work, and A J Reed was awarded the contract – the cost was not to exceed £2,250.

The committee attended to every detail of the preparations, from advertising for and interviewing candidates to be caretaker (John Walter Amey got the job) to giving instructions for rounding up the cows that kept invading the site and eating the newly laid turf.

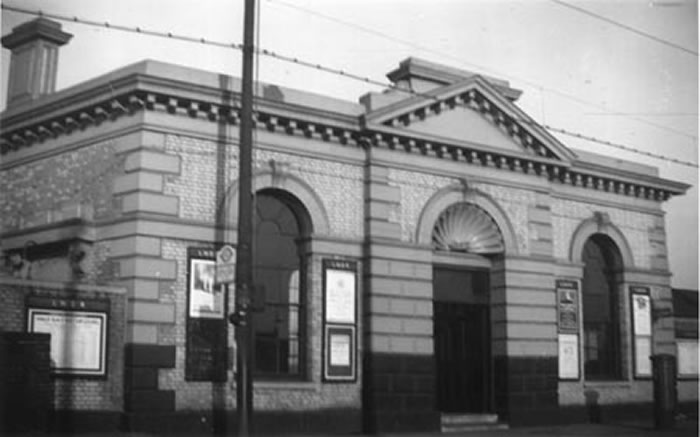

They prepared posters with the prices of different kinds of grave space, and placed advertisements in the local paper. Queen’s Road was laid out and surfaced with gravel. And finally, on 6th October 1872 the cemetery was ready, and official photograph was taken to mark the occasion.

At this time some funerals were very elaborate and expensive, involving many carriages drawn by black horses with black harness decorated with feathers, coffin bearers in black top hats swathed with veiling, and dozens of wreaths. For the funerals of people who had been well known locally, most of the neighbourhood would line the route of the procession. And there would generally be a reception after the burial, with special food and drink. Poorer people often put themselves into debt to pay for a “proper send-off” for a loved one.

And if funerals were elaborate, for those who could afford it, memorials were splendid. People wanted to show not only how much they loved their dead relative or friend, but also how important the family was, and what good taste they had. Most grave markers were in the shape of a cross, a pillar, or were a simple stone slab with an inscription. But In some Victorian cemeteries, for example Highgate, there are many memorials the size of small houses, with space for up to a dozen coffins.

At Queen’s Road there is only one such mausoleum, that of Harriet Hooker. Few people in the area could afford this kind of memorial. Indeed, only the moderately well off could afford any kind of stone for the grave of their loved one. However, it was not long before several monumental masons were in business in Queen’s Road.

Those who could do so, also paid to have the grave looked after. There were soon up to eleven people working at the cemetery. Most of them were gardeners – there were greenhouses on site, and families would pay a subscription to have a grave planted up with flowers each season.

Most graves, like that of Annie West were unmarked. The cheapest graves, especially those of the many children who died, had up to ten burials in them. And they were resold and reused after a set number of years.

When the cemetery was new, there were paths between the graves, and mature trees had been left in place. As time went on and space grew short, all but a few of the paths were used as grave plots, and many of the trees were felled.

Some of those who died in the two World Wars have their graves here, and many of these are marked with a special stone.

Now there is no more burial space left in the cemetery. And because there is a lot of gravel in the soil, many of the gravestones have subsided into the ground, meaning they now stand at odd angles. There are no longer any gardeners, and the chapels have not been used for services for many years.

But many people visit and tend graves. And this is a place that holds clues to the stories of thousands of people. Some of them are retold on this website.