Houses

In 1822 there were very few houses in our area. And the ones that did exist were mostly grand mansions or big farmhouses. Two of the four main roads that edge our area, Hoe Street and Marsh Street (now called High Street) were wide, elegant streets. Grandest of all was Hoe Street, where most of […]

In 1822 there were very few houses in our area. And the ones that did exist were mostly grand mansions or big farmhouses.

Two of the four main roads that edge our area, Hoe Street and Marsh Street (now called High Street) were wide, elegant streets.

Grandest of all was Hoe Street, where most of the houses were set back from the road and surrounded by gardens, and where many of the residents were rich City bankers or lawyers. Today only the Chestnuts and Cleveland House are left. But in 1822 Grosvenor House still stood – Grosvenor Park Road was later built along the route of the tree-lined avenue that led along its grounds. And the Cedars

Further south towards the Bakers’ Arms stood the Red House, bought a few years later by the Houghton family – they had made a first fortune as City lawyers, and were to make a second out of the development of Walthamstow. And northwards, on the site of what is now Cedars Avenue was a beautiful house called the Cedars. Visitors used to comment how peaceful Hoe Street was, and admire the lovely trees.

The houses in Marsh Street were slightly smaller, but still detached, mostly with six or seven bedrooms, and still big enough to have their own gardens and stables.

To the west, Markhouse Lane (now Road) was the footpath that led, first to the ferry and then to Tottenham. The Tudor Mark House stood to the west of the path, near where St Saviour’s Church is now, and was probably still standing, although dilapidated, in 1822. Along the lane itself were some small cottages, mostly lived in by farm labourers. This was already a poor area.

Over the years, Walthamstow stopped being quite so fashionable. The railway got as far as Lea Bridge Road in the 1840s, and property developers realised that more people could travel to work in London by train than there was room for on the stage coach.

Over the years, Walthamstow stopped being quite so fashionable. The railway got as far as Lea Bridge Road in the 1840s, and property developers realised that more people could travel to work in London by train than there was room for on the stage coach.

In our area, a few houses were built, some near Lea Bridge Station. And soon many of the local landowners realised there was money to be made by parting with some of their land. This happened slowly at first, but faster after 1872 when the railway line from London to Chingford opened.

The Cedars was one of the first of the big houses that first lost its gardens to development and then, after its owners died, was itself demolished to make way for Cedars Avenue and the surrounding streets. Many of the houses are bigger and more expensively built than the ones in streets that were developed a few years later.

The Cedars was one of the first of the big houses that first lost its gardens to development and then, after its owners died, was itself demolished to make way for Cedars Avenue and the surrounding streets. Many of the houses are bigger and more expensively built than the ones in streets that were developed a few years later.

But the houses in all the developments were very like each other. They were almost all terraces of two-storey brick houses. All had gardens to the front and rear, and most had a fence or wall at the front, a path leading to the front door and decorated plaster work round the front door.

Inside, the bigger houses had two reception rooms one in front of the other, with a kitchen and scullery behind. Upstairs there were usually three bedrooms, occasionally four. Some of these houses had an inside lavatory, and a few, a bathroom.

In the streets that were built in the 1890s, the houses were still brick terraces with three bedrooms. But they were very much smaller. Most of them had one reception room, with a kitchen behind and the scullery behind that. There were usually three bedrooms – this was considered essential so that a family could have a room for the parents, another for their daughters and a third for their sons. And there were no bathrooms, and the lavatory was outside. There was usually a bath and water-heater in the scullery, although some people kept a tin bath in the back garden, bringing it into the house on bath night.

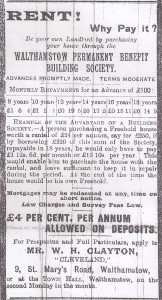

27 Chelmsford Road was, and is, one of these smaller houses. Its first known residents were a carpenter and his family – the boys in the photograph are almost certainly their sons. Most of the houses were “buy to let” investments – one estimate is that nine tenths of the residents were tenants. Many of them were young families, and it was not unusual for a couple, five or six children and sometimes another relative as well, to squeeze in.

If a family was hard up, a good way of making some extra money was to take in a lodger – the local papers are full of advertisements offering a room to let. Sometimes the advertisement promises “own bed” or even “own room”.