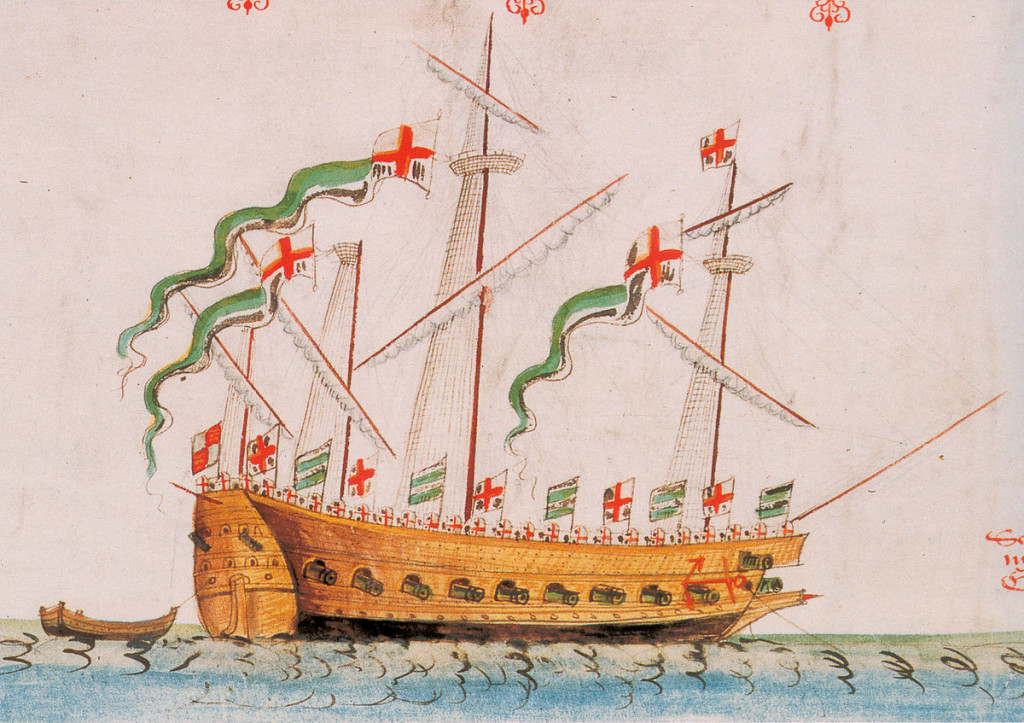

King Henry VIII was intent from his earliest days on bringing London into the premier league of world cities. At the beginning of the sixteenth century it had some way to go, battered as it was by decades of civil war. But the new young king was helped by the fortune left by his father, Henry VII. And one of the ways of building the country’s status was to make it an international centre for art, architecture, learning and music. So artists, scholars and musicians all over Europe found themselves in demand by the agents of the King of England.

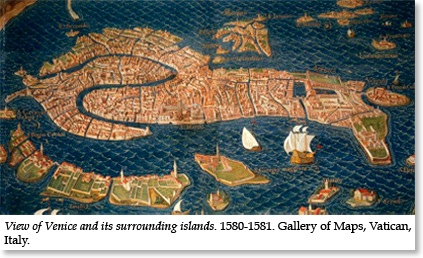

In Venice, the Bassano family were settled as musicians to the Doge. Probably of Jewish descent and originally from Sicily, Jacomo Bassano had moved to Venice in the early years of the sixteenth century. By the 1520s his six sons were employed not only playing and composing music but making musical instruments. Evidently they were adaptable in terms of what they played and of what they made – both wind and stringed instruments. It took several years of negotiations before most of the family finally moved countries and Courts, and became musicians to Henry VIII. Several of them set up as instrument makers in London, buying property near All Hallows by the Tower, which became their parish church. But as they became richer, they invested in country property.

In Venice, the Bassano family were settled as musicians to the Doge. Probably of Jewish descent and originally from Sicily, Jacomo Bassano had moved to Venice in the early years of the sixteenth century. By the 1520s his six sons were employed not only playing and composing music but making musical instruments. Evidently they were adaptable in terms of what they played and of what they made – both wind and stringed instruments. It took several years of negotiations before most of the family finally moved countries and Courts, and became musicians to Henry VIII. Several of them set up as instrument makers in London, buying property near All Hallows by the Tower, which became their parish church. But as they became richer, they invested in country property.

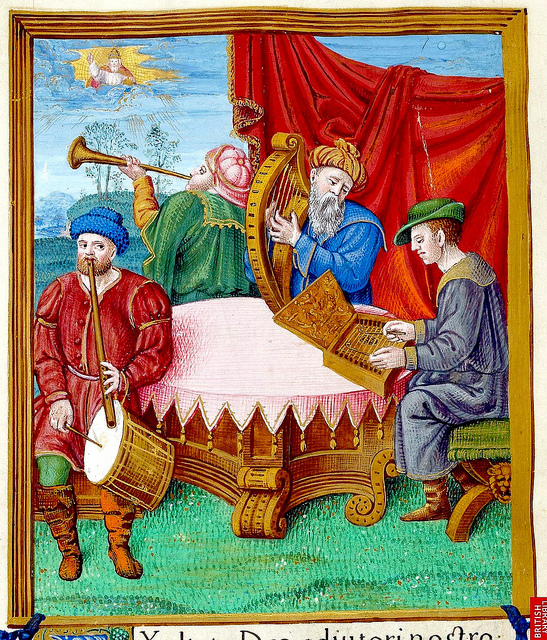

The Bassano brothers were employed to play both wind and stringed instruments at Court, and we know, too, that they produced and sold a wide variety of instruments. It is likely that the King, himself a competent player and composer, was among their customers. Some examples, bearing the family’s mark of three moths, survive and are playable today. A recorder recently turned up in a street market in New York.

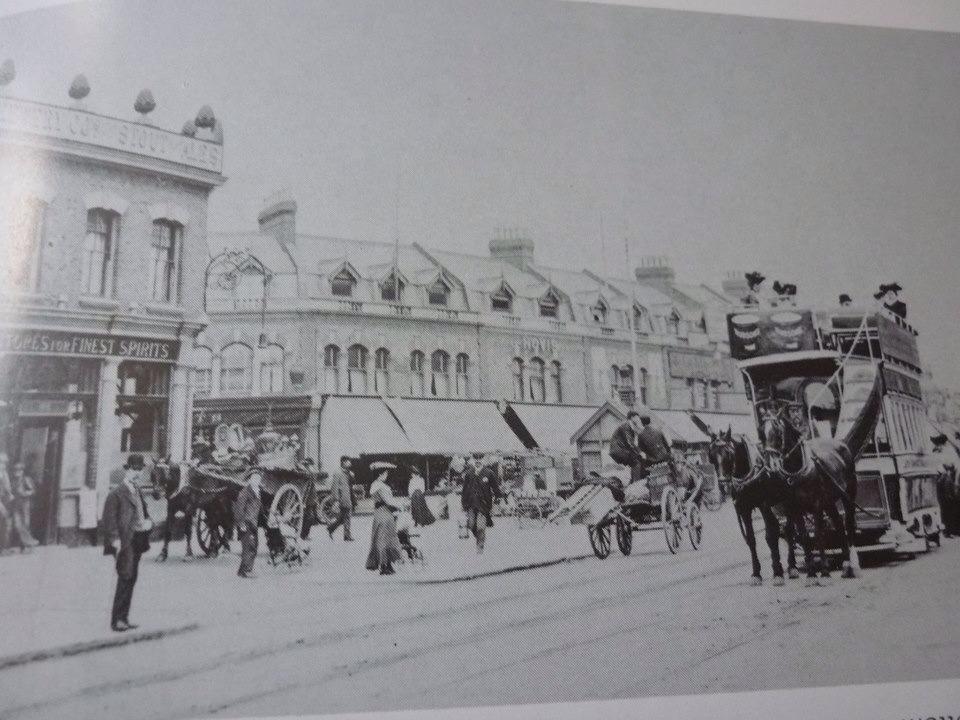

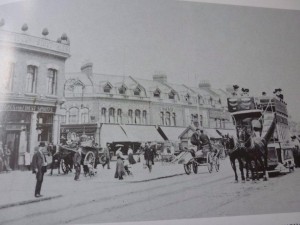

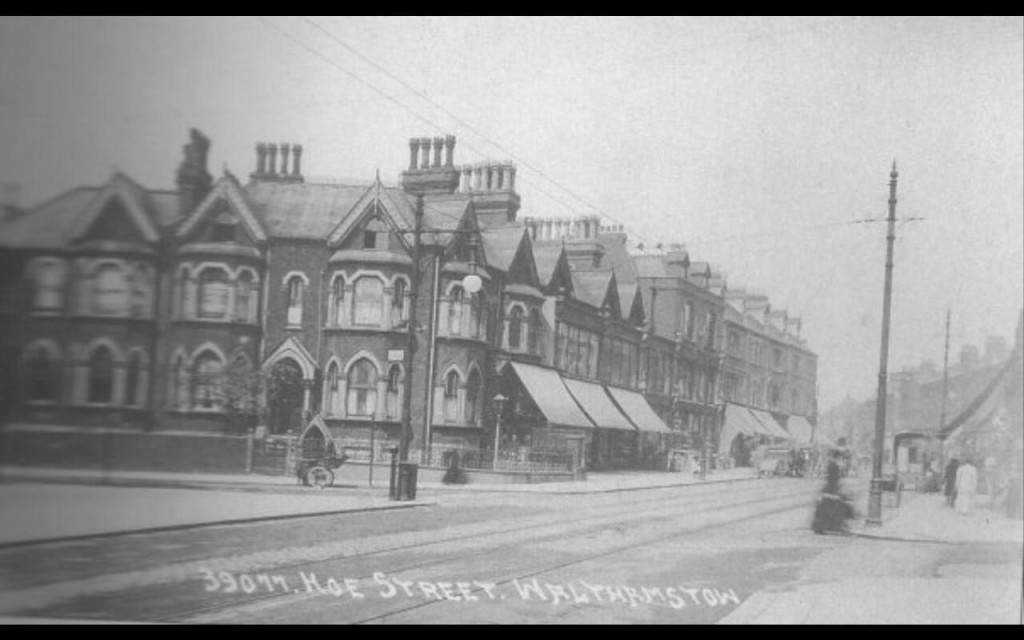

By the 1550s one of the Bassano brothers, Anthony, had acquired houses and land holdings in Walthamstow. His will mentions “messuages, lands, tenements and heridaments” in both Walthamstow Toni and Salisbury manors; two major properties were listed as “Fannes”, in Marsh Street (later the High Street) and “Starlings”. After Anthony’s death his descendants kept the properties, and were evidently still living in the area in the 1650s. As well as their Walthamstow connections, however, the later generations kept their connections at Court, until the start of the Civil Wars, with the All Hallows area of London and with Italy, where one of the first generation of brothers had returned and where his descendants continued to thrive.

Anthony Bassano was a person of some status. His Walthamstow property was substantial, and would have needed both domestic and farm servants to run it. This was a time when most music was performed in private – so the servants in the Bassano household are likely to have heard at least some music that was otherwise only heard at Court. This, then, was a Walthamstow household with international connections.

In later centuries the name Bassano has continued to crop up in the arts in Britain: there was a Bassano photographer in the Victorian theatre world, and in recent years there have been Bassanos playing in at least two London orchestras.